Oil discovery can make Suriname extremely rich, but also extremely poor

Suriname Strikes Oil: Balancing Riches and Risks in a Transformative Era.

Oil companies invested 600 million dollars in the search for oil off the coast of Suriname. Earlier this year, they finally struck gold. “Suriname will never be the same again,” they exclaimed joyfully. Will the country succeed in spending its oil dollars wisely?

For the past five years, Suriname has looked enviously at its neighbor Guyana. Oil companies there discovered one lucrative oil field after another during test drilling. Last week, it happened again: ExxonMobil announced a major discovery that brings the country’s oil reserves to about eight billion barrels. Per capita, that’s more than Kuwait.

Suriname isn’t quite celebrating yet, but oil companies Apache and Total did report the first major oil discovery in Surinamese waters on January 7. The British energy consultant Wood Mackenzie estimated the find at 300 million barrels of oil and 1,400 billion cubic meters of natural gas.

The Surinamese seabed geologically resembles that of Guyana, where 16 oil fields have already been found.

The prospects are good

However, at least three more test drillings are needed to determine the exact amount of oil in the ground and whether it is commercially viable, according to Lucia van Geuns, an energy expert at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS). “Only then can calculations be made.”

The outlook is promising as the Surinamese seabed is geologically similar to that of Guyana, where 16 oil fields have already been found. Test drillings are also taking place in multiple locations in Suriname.

Another positive aspect: the recently discovered field consists of relatively light oil. This type is easier – and cheaper – to extract than heavy oil and is much more marketable globally. “Suriname will never be the same again,” cheered Staatsolie director Rudolf Elias after the discovery.

From extremely rich to extremely poor: Norway vs. Venezuela

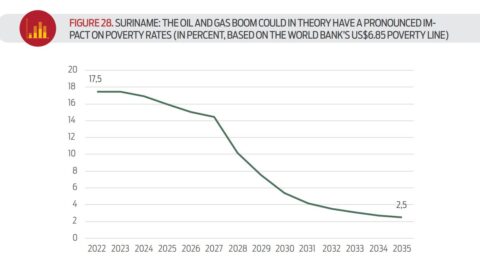

Elias may be right. It remains for Suriname to hope that the change will be positive. Oil can make a country extremely rich or extremely poor. Economists often cite Norway as an example of a country with sensible oil policies. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, which invests oil and gas revenues, now holds over 1,000 billion euros, roughly 188,000 euros per Norwegian.

On the other end of the spectrum is Venezuela, the country with the world’s largest oil reserves and once the richest country in South America. Venezuela became entirely dependent on oil revenues, and when oil prices plummeted in 2015, the country plunged into a severe economic crisis with hyperinflation and extreme shortages of food and medicine.

What can Suriname earn?

Staatsolie, which is fully owned by the Surinamese state, has the right to take a 20% stake in the oil extraction from the recently discovered field. It then claims a fifth of the revenues but also has to bear a fifth of the investments.

In addition, the Surinamese state receives royalties of 6.5%, and if the operation is profitable, Suriname also receives 36% of the profits.

“We still need to determine if there is indeed enough recoverable oil. But it could be that a few hundred million dollars will flow into Suriname soon,” says economist Winston Ramautarsing. “That’s significant income for a small country like Suriname.”

Which way Suriname goes depends on the strength of its institutions, says Van Geuns. The good news is that, unlike Guyana, Suriname has decades of experience in oil extraction. “Staatsolie is a well-functioning state-owned company in Suriname, with experienced personnel.”

Staatsolie director Elias aims to improve the financial discipline of the state-owned company with a partial IPO in New York or Toronto. If foreign investors come on board, it will strengthen oversight of the company, Elias expects. Moreover, with an IPO, Staatsolie can raise funds for oil production investments, estimated at 800 million dollars. Unstable governance Less hopeful is the governance of Suriname, which has become more corrupt in recent years and has incurred significant debts. Since 2015, Suriname has dropped from the 36th to the 73rd position in Transparency International’s global corruption index. In recent years, the Surinamese government borrowed so much money that it loses 38 percent of all tax revenues to paying interest.

Winston Ramautarsing, chairman of the Association of Economists in Suriname: “Based on recent history, I don’t think the government is ready to handle money wisely.”

Lessons from the past Interestingly, the downturn began because Suriname became too dependent on another commodity, namely gold, says Ramautarsing. “When the price of gold rose ten years ago, the state began to live beyond its means. That money was largely spent on consumption. When the gold price fell, a huge budget deficit emerged.”

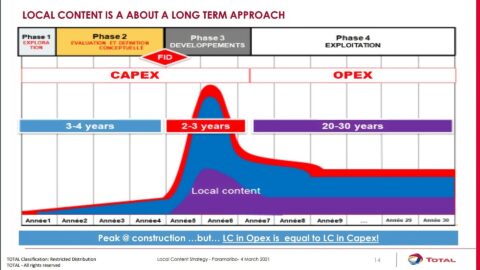

A glimmer of hope is that the Surinamese parliament passed a law in 2017 to establish a ‘Savings and Stabilization Fund.’ Ramautarsing emphasizes that it will take four to eight years before the first oil can potentially be sold.

“Hopefully, the future leaders have learned from the past,” he says. “But looking back, I honestly have little confidence in that.”

Date: 1 January 2024

Categories:

– DISCLAIMER –

LocalContentSuriname.com is een portaal waar ondernemers, bedrijven en stichtingen zich willen presenteren. Deze website is niet verantwoordelijk voor de inhoud die op deze pagina getoond wordt. Alle informatie die op deze pagina wordt verstrekt, moet onafhankelijk worden geverifieerd. Er worden geen garanties of verklaringen gegeven voor de juistheid van de informatie. Ga naar veelgestelde vragen voor meer informatie.